Space Elephants Across the Universe: Why Nobody Knows What's Going On With AI

Why it’s so difficult to understand what’s going on with AI in early 2026.

How To Become Wildly Successful in Business

The hard part isn’t understanding how to do it.

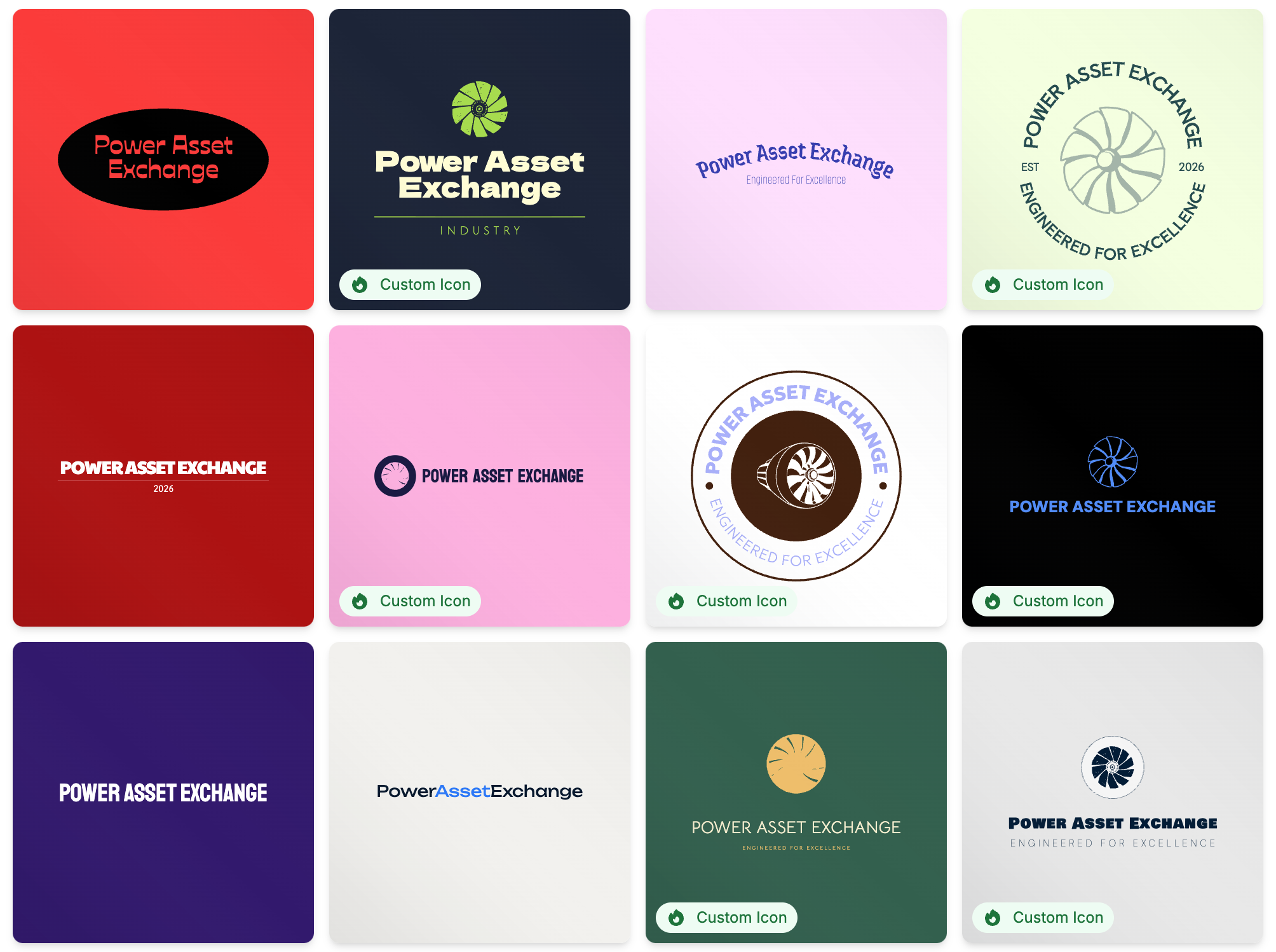

A Frustrating Adventure Trying To Design A Logo With AI

AI can do many things, but apparently not product logos.

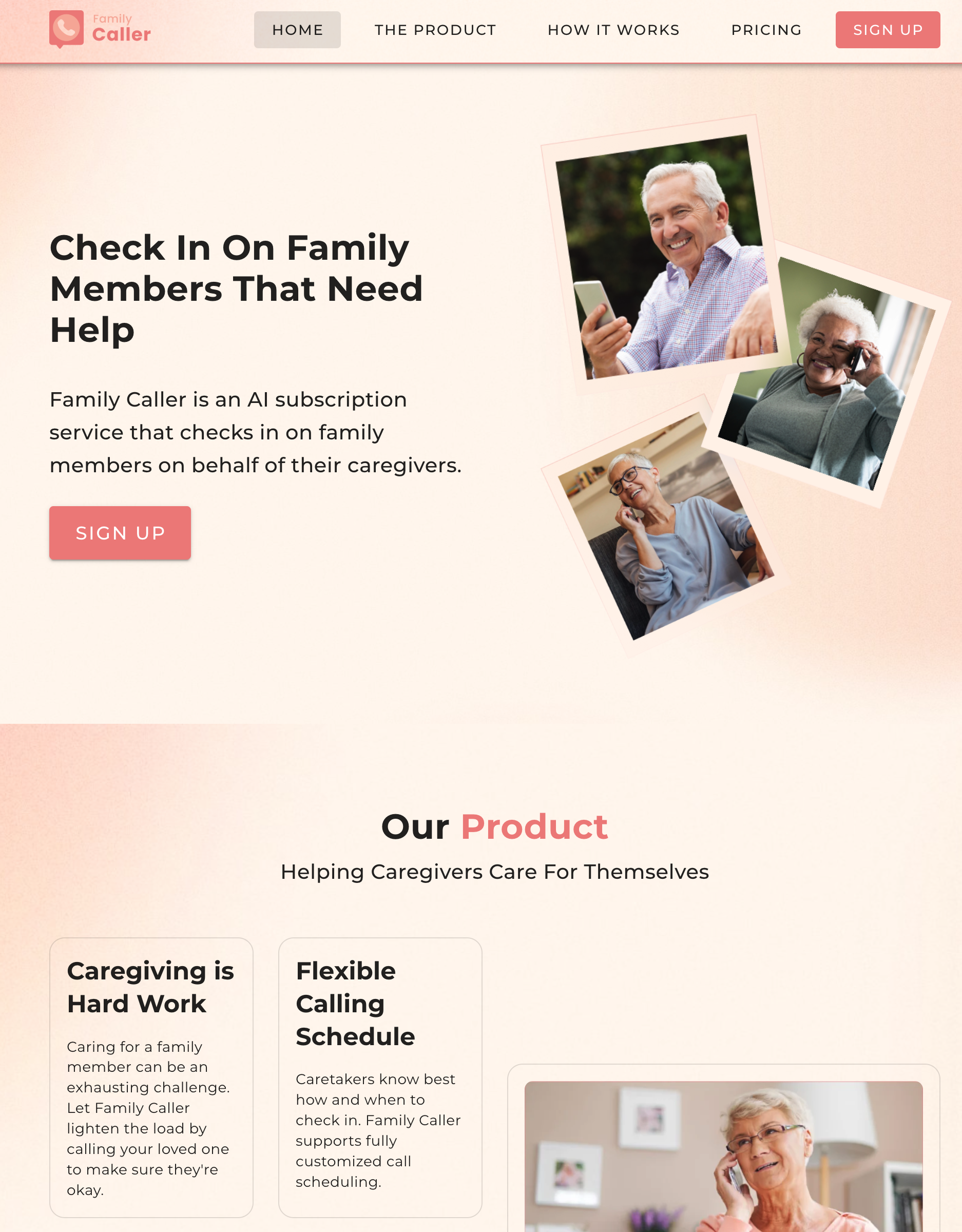

Why is B2C User Acquisition Broken?

In which the author discovers that vibe coding has made it a lot harder to build profitable companies.